Hi Aran! What initially got you interested in design, and what made you pursue it as a career choice? Was that something you knew you wanted to do from very early on?

It was very early on! I had an amazing GCSE and A-level design teacher, who just really brought design to life for me. It sounds a bit corny – but a good teacher made it happen! I didn't really return to design until my postgraduate degrees, as I did an engineering undergraduate degree first. A lot of the undergraduate uni courses in design didn't look too appealing to me at the time – so I thought, “Maybe this is something I can come back to later”.

What made you choose a different undergraduate degree? Did you find a degree programme that really spoke to you?

Yes – I actually think I preferred the degree programmes that allowed me to put off decision-making as long as possible! With the engineering undergrad degree I did – a four-year programme combined BA and MEng in Mechanical Engineering at the University of Cambridge – you could do pretty much every flavour of engineering all at the same time, and then you could choose to specialise two years later. I never ended up specialising at all – I just did a pick and mix of modules, which I think was great, as it was a bit closer to the US style of higher education, where you don’t need to choose one subject to stick to early on. I think that being 18 and having to make massive life decisions is a terrible idea – it definitely wouldn’t have worked for me!

How did choosing an engineering undergraduate degree influence your career choices further down the line?

Doing engineering really did shape a lot of decisions for me later on. I did four years of engineering during my undergraduate degree, and then I found a postgraduate degree: a combined MA and MSc with Imperial College London and the Royal College of Art. And at the time, the programme was pitched to engineers wanting to transition into the creative arts and design. So, it was a perfect follow-on course for me!

I think what I find interesting looking back now is that I did that postgrad degree to almost run away from engineering. But now I’m later on in my career, I can acknowledge that I'm an engineer! I don’t see myself as a designer, as I did when I first graduated, but I think that experience has enabled me to be a bit more creative.

Was there anything in particular that made you want to go into sustainable design and engineering, specifically?

I think sustainability is essential to my work – initially, this came from doing my undergrad degree in engineering. I had a semi-existential crisis of, "Oh, my whole career will be about making more stuff, and the world doesn’t need more stuff!" So my work has been about trying to resolve that conflict, and trying to find a safe place where the things you create are actually valuable. I think sustainability is the only thing worth working on, as an engineer!

A lot of my undergraduate classmates went to work for oil and gas companies, and in financial consulting – and I think something I really appreciated in the postgrad degree was finding my tribe. There were a lot of other people with the same mission-driven value set as me, whereas in engineering school the main driver seemed to be money.

Can you tell me a bit about how SafetyNet came into existence?

Sure! First off, I'm not the original founder. I met my colleague, Dan, during the Master’s degree about 10-12 years ago – it was this huge melting pot of people coming up with crazy startup ideas. The main problem that Dan wanted to address with SafetyNet was that fishermen were getting arrested for catching the wrong fish and bringing them back to port – there was an incident of that happening in Glasgow.

We (somewhat naively!) treated it as an engineering problem to solve. We now know that it’s a huge, multifaceted challenge that involves human behaviour, politics, and science.

That really led us to wonder, "Well, that's weird. Why is this happening? What can we do?" There is the feeling that we should probably be fishing less, which is valid, but we also acknowledge that fish is part of the diet of many people, all around the world. So, we wanted to know, why can't we just catch what we want and nothing else?

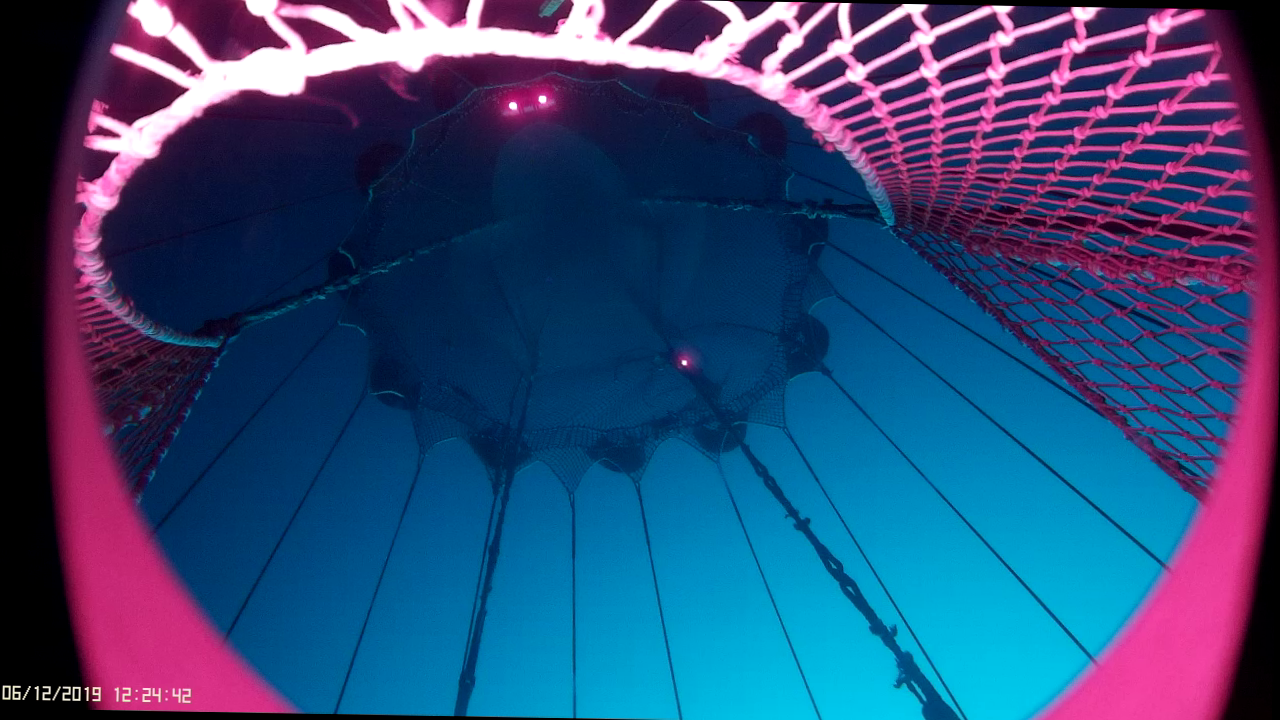

So we (somewhat naively!) treated it as an engineering problem to solve, to begin with. We now know that it's a huge, multifaceted challenge that involves human behaviour, politics, and science. But at that point in time, we found that, separately to this problem that fishermen were experiencing, marine biologists were also discovering that fish species can be directed by, and behave differently towards, different colours of light. So Dan put these two puzzle pieces together and thought, "Well, if we illuminate nets in different colours, can we segregate different species of fish depending on what we want to catch?" And that became our first product, Pisces, but it also became the principle of SafetyNet.

I was then brought on board to turn the idea from a fun principle into an actual product that would work; one that would survive underwater. So that really aligned with what I like doing – I like to work with people who've got a crazy idea, and help them make it real!

Can you tell me more about your role as Chief Technology Officer (CTO) at SafetyNet? What are your main areas of focus in your job?

It’s changed a lot as the company has progressed! I’d say the job involves a lot of zooming in and zooming out, multiple times a day. The “zooming out” is to make sure we're making the right things. This draws on my design skillset, which involves understanding human behaviour trends in biology and in industry, to guide my team and make sure we're creating the right products. There’s also a bit of entrepreneurialism too, because I also work on identifying business opportunities. Day to day, there’s a combination of desk research, and trying to talk to as many people as possible. This has weirdly been easier during the pandemic, as everything has shifted online!

We've got a lot of academic collaborators in universities around the world, and I maintain regular conversations with them, and go to conferences and events. That's more big, macro stuff, but right now, I'm doing a lot of the micro aspects of the job – a bit of engineering and design, and running a team of other talented people who do it!

My job as the team leader is to help them do their best work and to facilitate their well-being.

One thing I found about being a director of a startup a little way through its lifetime is that I had to acknowledge there are definitely other people in the company that are better at doing engineering than I am! And that's a great thing. My job as the team leader is to help them do their best work and to facilitate their well-being. So most of my day involves checking in with people, helping them if they’re stuck on something, and solving problems with them. Occasionally, they leave a little bit of engineering for me to do, which I really appreciate!

For example, we're releasing a new product later this year. I'm helping my team to design electronics, plastic parts, and metal parts for production, and make large quantities of these, so that we can assemble them into products for fishermen.

Overall, a key part of the job is being professionally organised, it seems! I have to be able to dive into someone's very detailed bit of engineering work, but then zoom back out to the bigger picture and think about how their component fits into everything else. I don't know if I ever actually learned that skill at university! I think it was something that I had to learn on the job.

Our income is currently driven by grants that we apply for and win, from the UK, EU, and some foundations in the USA. This is where design school comes in! It was the best preparation for applying for grants. I remember during two years of design school, every other week, we’d have to present and tell a story for others to critique. Learning how to condense a narrative down into something really simple, over and over, made me good at presenting, and taught me how to tell a story effectively when it really counts. Engineering school also helped with grant-writing through the sheer number of reports you have to write!

Does the people management aspect of your job come naturally to you? Or do you feel more at home doing the practical engineering tasks?

Well, I'm an introvert, so I much prefer getting my head down and doing stuff. But I've been delighted to learn that a lot of people in this situation have cracked this, and have written up their experiences for others to learn from! So, I've returned to my roots – I've been reading a load of books and watching a lot of webinars about how to be a good human when managing other people (Editor’s note: see below for Aran’s recommendations). I’ve come to learn that being a manager isn't something you're born good at, it's a skill that you can pick up. It’s actually been very comforting coming to that realisation!

You mentioned your colleague Dan Watson, who came up with the original idea for SafetyNet, and you’re now part of a team of 3 co-founders. How did you each assume your current roles in the company? Was that something you had to sit down and work out?

Oh, totally. It involved a huge identity crisis! The transition involved me, Dan, and our other co-founder, Nadia, who's Chief Operations Officer (COO) and looks after the running of the company, a bit like a managing director. Before we became a proper company, we were freelancing with Dan as the client. He'd won some prize money, he was able to pay us – so we worked for SafetyNet, amongst many other clients.

I think Nadia and I both liked working for SafetyNet so much, that Dan soon ended up the only client! And then he asked us, "So, should we get serious about this and do this properly?" There were a lot of complicated things to figure out, like company ownership. I think working out the responsibilities was relatively simple at that point, though: I was the only engineer, and Nadia was the only person with an MBA. Dan was the founder, with marine biology knowledge and the drive to go out and raise money from funders.

So, we fit quite neatly – and fell quite neatly – into our roles. I think a bit more ambiguity came as the team expanded: if other people are literally doing the important work, we had to try and understand our roles as leaders, and it took a while to figure that out.

You mentioned you have a new product coming out! Could you talk me through SafetyNet’s current products, and their development? Do you work on a few at a time, or does one product naturally expose a need for the next?

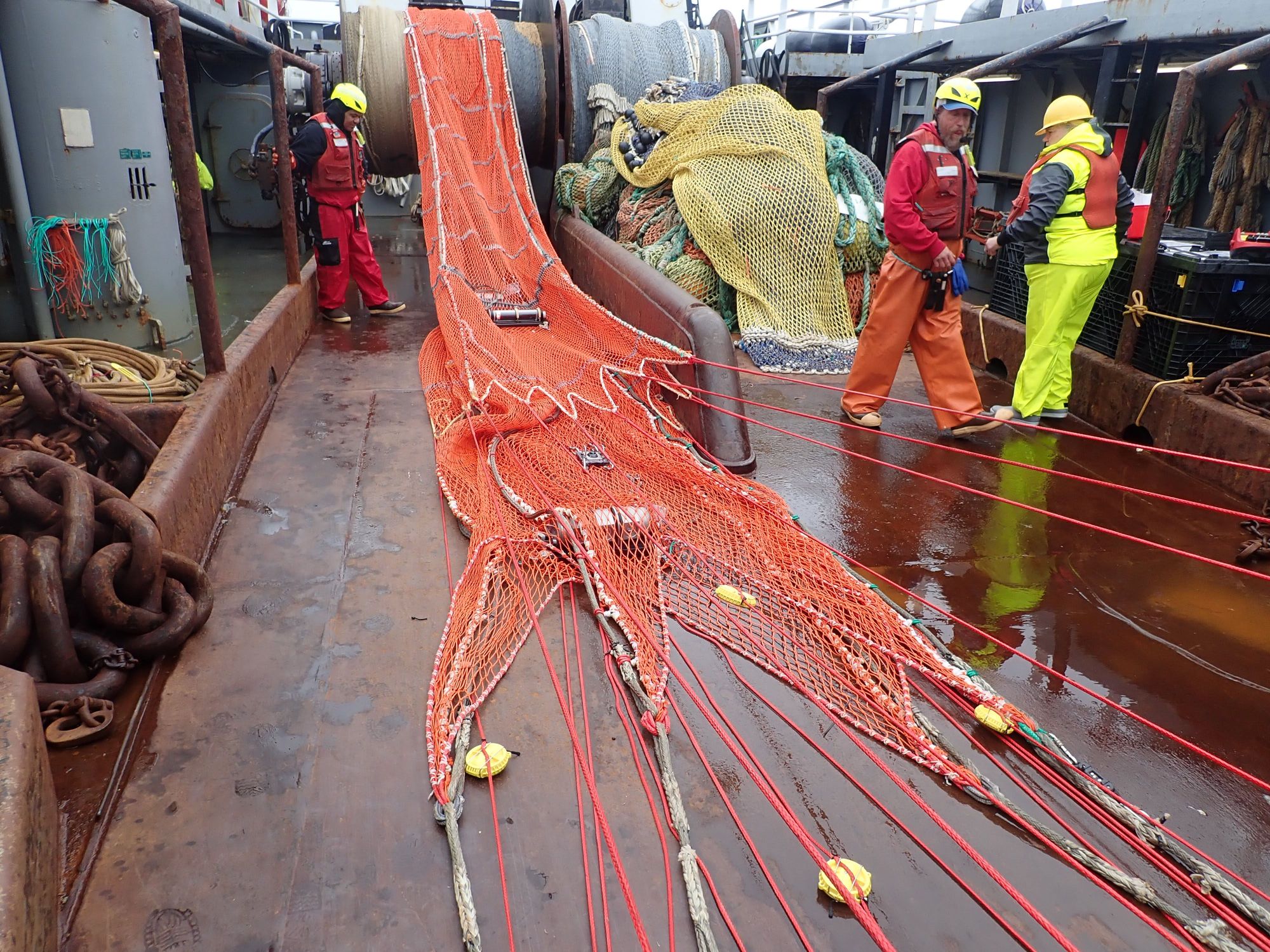

All of our products facilitate something that we call precision fishing. Precision fishing is enabling fishermen to catch only what they want, with no bycatch of endangered species, in the most efficient way possible – because out at sea you’re burning fuel, and you want to reduce emissions.

Most fishermen have never seen 90% of their job – which of course happens underwater – with their own eyes.

We started with the underwater lights (Pisces), which redirect different species in order to attract bycatch out of the net, whilst retaining the species you want in the net. As we were deploying these underwater lights to convince customers that they were working, we started to deploy GoPro on SCUBA cameras, alongside the lights. A lot of our customers asked, "Oh, can I buy the camera instead?" So we thought, "Well, this is a good idea!" We did a little bit of digging, and it turned out that most fishermen have never seen 90% of their job – which of course happens underwater – with their own eyes. They have to imagine, and use their tacit knowledge, to visualise how this really complex bit of architecture – the net – is behaving underwater, along with the fish species and size. So we began to develop an underwater camera that could assist with that visualisation.

There are dozens of things you can do to increase the sustainability of your fishing operation, such as the net material, its shape, and its geometry. But if you do make a change, you can't observe the effect it has, and this makes the pace of innovation really slow. So cameras could be a really amazing key to unlock this. In our early trials, literally in the first hour of video footage, the skipper of the boat we were on looked at the footage and said “Whoa, I'm changing that immediately.” It was a change that would better exclude non-target species. So he got on the phone with his net maker, and had a new net made within a month, based on the first-ever deployment of the camera.

Our dream is to be able to create an underwater weather report, that is linked to the species you're fishing. Some fish like to hang out at a certain depth, or where there’s a nutrient upwelling. If you can start to visualise that, it could guide you to avoid that bycatch.

And we've got a third product that's very early-stage, which is a sensor. Measuring the ocean is really important for modelling climate change and predicting the weather. Or, if you're operating a wind turbine for example, for calculating insurance premiums. Knowing things like the temperature, salinity, and density of the water, under the water, is really important. It's also really hard to measure stuff underwater, so there's a lot of very expensive kit being deployed by the Met Office and other universities to measure this. It's expensive, it breaks often, and we're just not getting the global coverage from it that we need.

At the same time, fishermen are putting equipment underwater all day, every day. So, we're making measurement equipment that fits onto the fishing gear. When it comes out of the water, it connects to the internet, and beams back their data to people like the Met Office – but it also creates some key insights for the fishermen, to incentivise their usage of the system.

Our dream is to be able to create an underwater weather report, that is linked to the species you're fishing. Some fish like to hang out at a certain depth, or where there’s a nutrient upwelling. If you can start to visualise that, it could guide you to avoid that bycatch, and fish only what you need and nothing more.

How far along are you in the design and production for this? You mentioned that one problem with the current technology is that it breaks easily. Is this the kind of thing you're working to overcome at the moment?

Yes. Making stuff that goes underwater and survives, is really, really hard! We try and make products that survive for at least two years – that may sound like a very short amount of time, but it's such a punishing environment.

Ultimately, we are a hardware company – but suddenly we’re having to do software and data science, and that’s a big learning curve.

When we first did the lights, we were able to develop and sell them, which is great – but we also ended up with an amazing team. They can design things that go underwater and survive, but they also understand fishermen's daily lives and their cycles of work. So now we've got a great resource to tackle other problems. We’re doing the camera first and we're releasing that in October, because it's such an immediate commercial win – running a startup is scary, and we need money!

The ocean data measurement product is a lot of work. It'll take five or ten years to be able to pull that off. We've got three of these measurement pieces on three boats at the moment, so that’s our very first toe dipped in the water.

Ultimately, we are a hardware company – but suddenly we're having to do software and data science, and that's a big learning curve.

Has anything surprised you about your work with SafetyNet so far? Was there anything that you thought, "Oh, I wish I'd known about that before getting started with this"?

Yes, a few things have really surprised me. The first thing, that we’ve already talked about, is finding out that you can learn a lot of people management skills. Some people have actually dedicated their lives to upskilling others about this! That was a really great surprise.

The second thing that has surprised me – and this would apply to anyone in the company, not just the directors – is that working in a startup, you can't just be an engineer, or just be a business analyst, or just a comms manager. You have to roll up your sleeves and muck into every little thing that needs doing!

This can result in someone who's an intern doing something of absolutely critical importance, or it could result in a director having to do something quite banal or dull – but everyone in the company is united by this environmental mission, and everyone knows what needs to be done. So it was a surprise that the nature of the work is so variable – it's a really mixed bag. When I graduated from undergrad, going into a big engineering company and becoming hyper-specialised at one thing was the fashion – but that's really not the case with a startup.

You've touched a few times on all the skills that you've been learning around leadership management, and learning what it means to become a good manager. Are there any particular courses you've done, or anything that you've read or watched, that you’d recommend to others in your position?

Yes, there’s a few things I’ve done that have been really valuable to me. The first thing is joining a society or institute, particularly for engineering – so I was a member of the Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET). Their training courses are usually really good – it's worth asking around though, as I have encountered a few courses that are a bit old school. It’s a good community, though, so it's very easy to ask for help. And if you can get your employer to pay for it, then all the better!

There’s also a book that really helped me: it’s called The Manager's Path. The title makes it sound dull, but it was written by the CTO of Rent the Runway. It’s structured to replicate the path you take: Chapter 1 is about getting your first intern, and then it ends with becoming CTO. Each chapter deals with a different challenge: answering the question of "What do I do now?" or, "What should I be thinking about? How do I manage managers? How do I manage a first starter?" It's a wonderful collection of experiences that I found really helpful.

What does a typical day look like for you at SafetyNet?

The catch-up meetings with small teams usually structure my day. I facilitate these meetings, which tend to be about half an hour long, and I go around each genre of engineering and ask, "So, what are you working on? Is anything blocking you? Do you need any information?" Then we tend to have a conversation around those three topics. This helps me keep track of what's going on, but more importantly, it helps the team stay connected, even though we're working remotely.

There might be one or two of these meetings per day and throughout the week. Everyone in any company has their A team – the people they work with most. For me, that can change: it can be the other co-founders, if we're working on strategic matters. I might be doing a lot of working sessions with the co-founders to tell a new story, to attract more money, or report on something cool that we're doing.

This week, my A team is the rest of the engineers and designers, so I’ll be working quite closely with them to do a particular task. I’m working remotely, so there are a lot of work video calls, but we try not to call them meetings. They’re just working sessions, I guess!

Very rarely, there'll be times when I'll just go into the lab, if I'm in London, in the studio, and do some experiments for myself.

How did the company have to adapt to COVID – did you make any major adjustments to how everything works?

I think there was one huge change that precipitated loads of little important changes – it was when the government announced its furlough scheme. We were trying to decide whether to take advantage of it or not. We put it to the company – we opened up all the finances apart from everyone's salaries and said, "This is the bank account. This is how much time we have until the bank account hits zero. What can we do?"

So, as a company, we went through a communal decision-making process that resulted in furloughing everyone, including ourselves, and that led to a lot more major decisions being made in a less hierarchical way. A lot of company processes now work like this: whoever's accountable will solicit advice from the people who want to offer input, or the people who are most important. This has led to a few other things – like we're now part of the four-day working week trial.

We decided to carry on working in a hybrid-remote way, but with a major presence in the London studio. We're currently experiencing a backlash against that, but that’s good because people are reflecting on what's working and what's not. It's still this open decision-making process, which is slow, but I think everyone feels really empowered, which is great.

I saw that you were advertising a position at SafetyNet recently. Can you tell me about your recruitment process? What do you look for in a candidate, and is there anything that immediately stands out to you in an application?

Yes – being mission-driven, purpose-driven, is the number one thing we look for. If someone's very productive, but they don’t really care about what they're working on, then that's going to be a really big cultural mismatch with the rest of our team. I don’t mean you have to love fish or go fishing every day or anything! We would just want a candidate to express interest in doing something purposeful. You can see evidence of this as early on as the cover letter or a CV – it’s in the story people tell about themselves. We’ll ask people some probing questions about making sense of their experiences, and what they want to do next. Their driver and purpose usually comes out through their answers to those questions.

How do you work on your industry knowledge and CPD, and keep up with new developments in your line of work? Are there any valuable resources you use that you’d recommend to others?

I think historically, I've learned the most through making things myself, and doing little side projects. One of my favourite places to learn about new techniques are other communities of makers, as opposed to, say, academic journals. There are blogs like Hackaday – I tend to gravitate towards communities that are more on the fringes of engineering. There's a festival called Electromagnetic Field, which is an incredible gathering of people doing really weird engineering! And I think weird is what I'm looking for, I suppose. There are also proper conferences – if you want to get into ocean technology, there's a conference called Oceanology in the ExCel Centre every year, which is a big playground of cool robots, satellites, and tech.

Also, I get a lot out of just hanging out with our customers. I get regular opportunities to just go on the harbourside, go on people's boats, and see people's lives as they are.

Do you have any advice you’d like to share with new graduates or early career professionals in design or engineering?

Sure – something that's really stuck with me from one of my previous mentors was, towards the end of her career, she'd always say "I don't know what I want to be when I grow up." That really had an impact on me. I think when you're just graduating, it’s important not to assume that your education is over. Try and find experiences where you can keep learning, and that'll set you up really well for life.

A more practical piece of advice is, if you've had conversations with someone and you've got a lot out of that conversation professionally, see if you can make it a regular thing. Just speaking often with someone who's “been there and done that” is really helpful. It aligns with the “carry on learning” message – after you’ve left formal education, you'll run out of teachers because you're not in an academic environment anymore. So finding mentors – or even just a friend that you can have conversations with – is so valuable. You can be pretty sure that anyone who's in a good place with their career is there because they've also received excellent advice from a mentor!

That’s sound advice! Thanks for talking to us, Aran!

Related articles

Do you want to pursue a career in sustainability? Check out these articles next!

✏️ Thinking of pursuing a career in the environmental sector? See the latest job vacancies on environmentjob!