Would you like to introduce yourself?

My name is Dominic Price. I'm the Founder and Director of the Species Recovery Trust. I'm predominately a species conservationist, but for the last 15 years I’ve also been delivering botanical training and have written a couple of field guides. I also have a totally separate life working as a musician!

Could you describe briefly what the Species Recovery Trust does?

The SRT was set up with the sole aim of saving 50 species by the year 2050.

There were two main driving forces behind this - firstly, that it was rapidly becoming clear that the current mass extinction crisis was worsening from year to year. Having initially thought a lot of this loss had happened in the post-war years, I was startled to discover that when I was born there were twice as many species on the planet. This was very much our problem, and our moral duty to fix it.

Secondly, we felt the conservation movement as a whole seemed to be shifting rapidly towards landscape-scale large conservation projects. While these projects were going to deliver some fantastic gains in these landscapes, it had left the future looking rather bleak for ultra-rare and scattered species that fell outside these areas.

How did you get started? What was your motivation to get into conservation initially?

As a child my love for nature was very much fostered by my parents, and despite growing up in London we spent most of our free time in the fantastic range of green spaces our neighbourhood offered, giving me a keen interest in nature from a young age. I was an avid ‘collector’ and soon built up a collection of stones, bones, skulls and seeds which formed the backbone of what I referred to as my museum (to which I am still making additions 40 years later)

As I entered my teens this love of nature became tempered by the increasing realisation that all was not well in the world, and across the globe we were losing great swathes of rainforest, whales were still being hunted in the Southern Ocean and even in this country nature was disappearing at an alarming rate.

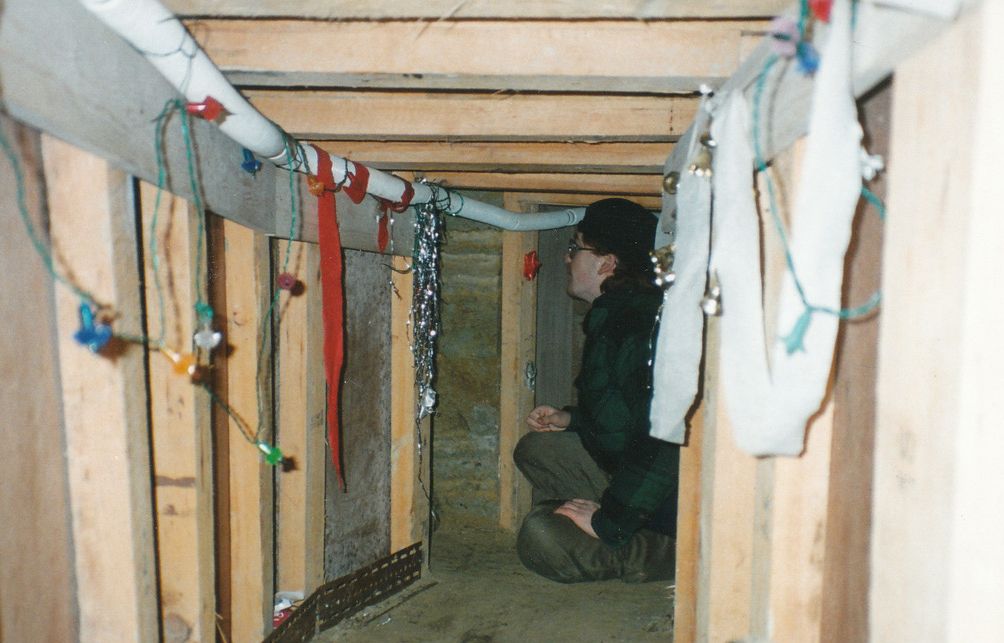

Somewhere in my late teens I discovered a book called ‘The Monkey Wrench Gang’ by the American author Edward Abbey (a book I can’t recommend enough, if you can get hold of a copy!). This book was a real epiphany and opened my eyes to the world of non-violent direct action in the name of saving the planet. I then spent several years on the fringes of the EarthFirst! Movement, which was very much a progenitor of Extinction Rebellion.

It was an exhilarating but mentally and emotionally draining time, which saw the high profile Twyford Down, M11 and Newbury bypass road protests, plus a plethora of other issues to be fought, from arms dealing to oppressive regimes to foxhunting and much else besides!

By the late 90s I was starting to feel hollowed out by all of this and decided that a life as an activist was not something I could sustain. I have immense respect for everyone involved in this movement and I think few people realise just how much commitment and bravery it takes. I still believe non-violent direct action is the driver that affects so much of the changes we need to achieve in reaching a fairer and more sustainable society, and am deeply worried by current plans to further criminalise those who take part in such actions.

What did you study at university?

Well, that’s a whole other story! I knew I wanted to do something for the planet and had put down a bit of a hodgepodge of courses with the term ‘environmental’ in them. When I came to the exam results, to my surprise the three years I spent playing and touring in a band was weirdly not taken into account and I failed to get into any Environmental Science degrees. Thankfully, Reading University had given me a much more generous offer to read Environmental Biology, and after a year working on conservation projects in Australia, I started at Reading in 1992.

Having always thought zoology was where the excitement was, I remember my first botany lecture from the inspirational Michael Keith-Lucas, all about the ecology of the rainforests, and from that point I was pretty much hooked!

In the final year of the Reading course there was a choice to attend either a zoology field trip in FSC Millport, which was renowned for time spent looking at the behaviour of inter-tidal limpet populations, or a botany field trip to the south coast of Spain, which was renowned for sunshine, sangria and skinny-dipping and (there was some mention of the endemic flora too). This represented one of the easier career choices I had to make, and a few months later I found myself in a smoky tapas bar in Almeria, armed only with a rudimentary knowledge of Mediterranean botany, and my guitar.

I say I didn't have any plans for the summer, I didn't have any plans for the rest of my life!

By chance a lecturer on the MSc course, Richard Carter, played the squeezebox, and after several slightly drunken play-alongs he enquired whether I had any plans for the summer after uni as he was short of an intern for that field season. Not only did I not have any plans for that summer, at that point I didn’t have any plans for the rest of my life, so I was delighted to say yes.

I spent just under 4 months working alongside Richard, carrying out well over 1,000 quadrats (it certainly felt like that) but it was the best immersive start to a botany career that you could hope for.

On reflection there was some poetic justice that the same guitar which had led me to fail so miserably in my A-levels had now got me on the path to becoming a working conservationist.

What was your first full-time job? How did you get your first break?

After the field season came to an end, I accepted the inevitable, moved back with my parents and started volunteering with Dorset Wildlife Trust and Dorset Environmental Records Centre, half-heartedly applying for jobs which all required far more experience than I had. The volunteer work was mind-numbing in places, involving transferring all the typed and handwritten SNCI records onto a new computer database, although I did end up with all the Latin plant names so firmly etched into my brain that they are still lodged there 30 years later.

While I was volunteering, a distinguished botanist called Robin Walls had made enquiries as to whether there were any spare botanists who might be able to help him on a large-scale farm survey project, and thankfully someone remembered me mentioning my previous fieldwork. Robin took a great leap of faith in employing me, and I soon was able to develop my lone surveyor skills (although I still remember one excruciating moment where I mis-identified some vegetative Lesser Stitchwort as a type of grass).

The work was a great chance to be outdoors, but after a few months of endless days out surveying on my own, combined with a painful breakup with my university girlfriend, the loneliness of the long-distance surveyor started to kick in.

I had spotted an advert for field studies instructors at an unlikely centre called ‘Superchoice’, on the Dorset coast, and applied there, predominantly as it looked like an existence much closer to student life compared with what I was currently doing. I was accepted, but on arrival I think most of us realised we had been slightly misled. Although there were some field studies going on, the vast majority of your time would be spent on the quad bike tracks, and possibly the abseil towers if you behaved well. The fear and adrenaline of working very high up dangling off a rope was soon subsumed by the intense and choking fear of being put on Thursday night ‘disco duty’ which involved a near compulsory activity of being on stage demonstrating the moves to various dance hits.

What did you do after your stint as a field studies instructor?

I loved the elements of field studies that I did teach, but after getting briefly transferred to a Pontins camp (owned by the same company) decided that I really needed to get back to my studies and applied to a Masters course at Lancaster University. I had become vaguely acquainted with the National Vegetation Classification system while working as a surveyor, and the chance to study under the architect of this, John Rodwell, seemed too good to be true.

I had a fantastic 9 months at Lancaster, lapping up all the lectures and seminars and making up for my errant younger years of getting away with as little work as possible. I actively avoided playing in another band and the distraction I knew that would provide, and instead spent every weekend exploring and botanising the wonders of the Lake District.

Growing up on a heady diet of David Attenborough and BBC documentaries about the rainforest, I had naturally presumed that this could only be the zenith of any botanist’s career.

Towards the end of my course, I spotted an advert asking for Field Assistants to come and work in the Eastern Arc mountains of Tanzania with the charity Frontier and was thrilled to be offered a post with them.

Growing up on a heady diet of David Attenborough and BBC documentaries about the rainforest, I had naturally presumed that this could only be the zenith of any botanist’s career.

Three months later, spending my 40th morning putting on wet clothes that had failed to ever dry out after months of non-stop rain and mist, tending to injuries which despite all precautions had started off as scratches and were becoming suppurating wounds and dreading yet another breakfast of a watery maize-flour porridge before heading off for a 5-hour trek to set up a new set of transects, the naivety of this original decision was really hitting home!

Don’t get me wrong, the rainforest can be a remarkable place, but in this mountainous and remote part of East Africa the forest was a deeply oppressing place, where the sunlight rarely reached the forest floor, and the joy of moments where it stopped raining was fleeting before you were attacked by hordes of insects.

During this time, I became near obsessed with the British countryside I’d left behind, and the meadows and heathlands which had seemed so unexotic compared with the wonders of the tropics that awaited me, now in my head took on the most wondrous sense of nature at its finest! After serving my 12 months I was back in the UK, and more than grateful for everything we had – the birdlife, an early morning spring frost, the autumn leaves – I could go on!

What was next?

At this point I decided the most fulfilling work I had done was as a botanical surveyor, but I just needed to find a full-time job doing this, where I could start renting a room, and get to spend time with other surveyors. I was very fortunate to get the first job I applied for with a consultancy firm in Stroud and moved to this remarkable town in the Cotswolds. There followed many happy months working alongside some top-level botanists and widening my skills into grasses and bryophytes. The work was curious as it was starting to strike me that most of what we were surveying was likely to be built on, but the excitement of honing my craft and working with a great team of people made all of this worthwhile.

I was going to end up back on a road scheme, but this time as one of the people in yellow jackets I had spent so much of my time plotting against just years earlier.

Six months later I was told I would be transferred full-time to be an Ecological Clerk of Works on the construction of the M6 Toll road. Through some horrible twist of fate, I was going to end up back on a road scheme, but this time as one of the people in yellow jackets I had spent so much of my time plotting against just years earlier. I spoke to the project manager and said that for various reasons I was really really keen to not work on this project, but was given the bleak choice of either doing what I was told or leaving the company. It was a terrible choice to have to make, but in the end, I decided that as all the previous protest campaigns had ultimately failed to stop any of the roads - although the road building programme had been scaled right down as an indirect result of them - maybe it was time to see if one could affect the system from the inside.

For my first few weeks on site, I was a nervous mess – we were taken out on site with a double ring of security guards, and I lived in dread of coming face to face with protesters who might recognise me and collapse the whole house of cards I had built. In the end I had little to worry about – the M6 Toll was one of the least protested road schemes ever (perhaps due to a local population who already lived in the shadow in the M6, M5 and M54 and were more accustomed to growing up with the hum of traffic than the call of birdsong).

I spent a few more years in commercial consultancy but always felt like I was something of an outsider, waiting for my past to catch up with me. Although I loved working outdoors and the challenge of the problem-solving elements of the work, it was an uneasy time. Plus, I think the fuss I had created initially by refusing to work on the M6 Toll and then a subsequent refusal to work on the M1 widening had probably tarnished my prospects early on.

Every answer I had given screamed to them that I should be working in conservation and not consultancy

After 5 years I applied for a job with another consultancy firm in Bath, where several of my friends lived. The interview went well and I was excited when I received a phone call the next day. They said they liked me a lot, but they weren’t going to offer me the job, as every answer I had given, plus my background, screamed to them that I should be working in conservation and not consultancy.

This was the Damascene conversion I think I had probably been waiting for and I suddenly realised I had, indeed, accidentally drifted into completely the wrong career.

How did this change the direction of your work?

Seven months later I was delighted to be offered the post of Back from the Brink officer with the renowned charity Plantlife.

The work at Plantlife was beyond exhilarating, I was handed a portfolio of rare plants, some of which I’d barely heard of, and under the auspices of Lead Partner on the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP), and given a fairly open-ended remit to get out and start saving them. This started an intoxicatingly intense relationship with many of these species, where I got to know individual plants and could start to perfect the techniques to accurately survey, monitor and manage the habitat for them.

Sadly, it appeared that I had arrived rather at the tail end of this work, a bit like getting to a party when the DJ is already packing up and there’s people stacking glasses. Within 4 years the UKBAP was largely scrapped, with barely any of its bold post-Rio targets achieved, and our efforts were moved onto what felt like years of re-packaging this work into ever more complex layers of acronyms, BOAs, IBDAs, NIAs, all of which felt like a vast distraction from the actual job of being there on the ground saving species.

Having realised I had inadvertently developed quite an intense personal philosophy of how important it was to stop these plants going extinct, I then realised the best way to do this was likely to be outside the charity, and with a small group we set about building a new organisation, dusting off many of the old BAP targets and updating them for a new decade.

How would the charity be different from previous work you had done before?

From what I had seen of the conservation sector I was struck by just how funding-led it was (which is fairly obvious) but it seemed to almost entirely consist of a series of quite costly projects, which would run as long as the funding lasted, at which point the work would be wrapped up and the project officers would either come to their end of their contracts or have to be moved onto the next initiative. This meant in reality people were spending the last crucial months of projects feeling incredibly mindful of what was going to happen at the end of it. While this could work for organisations, and I have huge respect for the efforts made to ensure project officers nearly always had new projects to move onto, I could see this proving catastrophic for some of the species on the ground, which really just needed years and years of the same level of work to keep them alive.

From the start of the SRT we wrote 25-year workplans for every species – many of them quite low level, with years where we would do nothing apart from monitoring and observing. This would give us a chance to trial new techniques, and then have up to 5 years to observe how successful we had been, before we used any of them on new sites.

For the first year we operated on about £200 a month, while running the bare bones of a national conservation programme.

This was obviously going to be a challenge to fund, so we set about working out a way to minimise our costs as much as was physically possible. I took on gardening jobs, to try and stay fit while putting food on the table, taught myself web design, and got the first website hosted by a friend in return for guitar lessons. For the first year we operated on about £200 a month, while running the bare bones of a national conservation programme.

I was already running residential botany courses at the Kingcombe Centre in Dorset and decided to expand this to running courses for the SRT. I think we had 5 bookings on our first course, which was tremendously exciting, and this rapidly grew into a much larger training programme, where we now train around 800 people each year.

What were the advantages of this approach?

We still get about 50% of our income through training and the sales of the Grasses Field Guide, and this level of unrestricted funding gives us the ability to work on any species, anywhere in the UK, at any timescale we choose. This means we can both plan extremely long-term work, but we can also set up and start new projects in a matter of days. We have been very lucky to attract larger funding from some very generous funders, many of whom now regularly support us, and this has put a lot of ‘flesh’ onto the bare bones of our project. In 2020 we were very excited to start our first projects in the overseas territories, working in conjunction with the St Helena National Trust on some of the Island’s remarkable endemic insect populations.

What's your favourite SRT site?

I think this would have to be one of the Marsh Clubmoss sites. This is a species that has survived almost unchanged for 400 million years, which when you spend time really thinking about it does blow your mind a bit! We knew populations generally occurred on trackways through wet heath and mires, but it started occurring to us that this could simply be the locations where they were being recorded as people were tending to see them there on walks, and not reflect the true distribution. One afternoon in the New Forest I was mucking about with my daughter in a perilously deep bog, when in the distance we saw this huge carpet of shimmering red Sundews, growing as a floating mat in a deep mire pool.

We wandered closer to get a good photo, and then realised we were almost surrounded by Marsh Clubmoss plants. There was no good reason that anyone would have ever walked this far into the bog, and it turned out to not only be a new discovery but was in fact one of the biggest populations in southern England. It has also given us a whole new understanding of the types of environment these plants can thrive in, and is a site I re-visit regularly, both to monitor and just to bathe in the wonder of!

Where do you see the conservation sector going in the next few years?

That’s a really tough one! I think largely it will probably continue in a similar vein, but with re-wilding and re-introductions very much growing on the agenda, it will need to work out how these can best integrate into and modify existing initiatives.

What I would really like to see is a much better set of funding principles. I think over the last decade we've become inured to eye-wateringly large sums of money getting poured into short-term projects, and I’ve seen so many highly skilled and passionate colleagues who just get their momentum going on projects before they come to an end, and then have to start all over again on the next one.

If you compared two projects where one had had a budget of £5,000 annually for 10 years, and the other had a one-off payment of £50k with the understanding it had to be spent by the end of that financial year, I think the results on the ground would be striking!

What’s this last year been like for you?

Well, it’s certainly been a challenge, but quite mixed. In terms of a lot of our work the fact we already all worked remotely from home and did most of our fieldwork alone meant we could keep doing a fair bit of this – it was only when the pandemic really kicked in, I realised just what a socially distanced lifestyle being a botanist is!

We had a bit of a scary moment where we realised we wouldn’t be able to run any training courses in 2020, so our carefully developed business plan started to crumble around us. Initially I could see no way as to how you could teach people to identify plants in the wild through a computer screen, but after a few months of attending other organisations’ online training courses and seeing the various advantages and pitfalls of teaching on Zoom, I started to think that maybe we could make it work.

Once we started developing the courses, using pre-recorded talks which took up to a month to film and edit, the huge possibility of what these courses could deliver became clear. By using our huge stock of images, we were suddenly able to compare species through different months of the year, to whizz instantly from damp mires to dry chalk and look at similar looking species and present a much wider array of info than we could do in the field. We’ve always been criticised for the southern bias of our courses and it’s lovely to welcome people from the furthest reaches of Scotland and Ireland, and even Europe.

The bookings have been incredible (huge thanks to Environmentjob for much of this) and in a short space of time we were able to fill the financial shortfall we suffered in 2020 and get all our species programmes back up and running for 2021.

We are hoping to once again run field training this summer, but we will also be continuing to develop our online programme in parallel.

Last question - with all your experience, what's a skill that really makes people stand out and increases their chance of success in the conservation sector?

There are so many people trying to break into both the world of consultancy and conservation, and it’s really tough. When I look back at my early career I’m struck by a) how utterly random it was in terms of meeting the right people and b) how privileged I was to have parents who welcomed me back home well into my late 20s, allowing me to drift between contract jobs and unpaid voluntary work.

All our current project officers (except one) are people who have approached us, shown a clear passion for conservation, and probably more than anything have just been outgoing and friendly. I think we all know skilled ecologists out there who have clearly spent so much time learning taxonomy that some of the more basic social skills have fallen by the wayside!

As much as our work does involve some fairly detailed knowledge of species ecology and land management, I’d still say 80% of it is about getting on with people, so it’s vital you let this shine through in any applications and interviews you have.

So, don’t be afraid to take wrong turns, as they all form part of the person you later become, develop a passion for a specific area of conservation, and most of all just be the most friendly person you can be!

Failing that, take up the guitar and form a band; you never know where that might lead you…

🌿 Look out for SRT courses on our courses & events page.

✨ Follow what Dominic and the SRT are up to on Twitter.